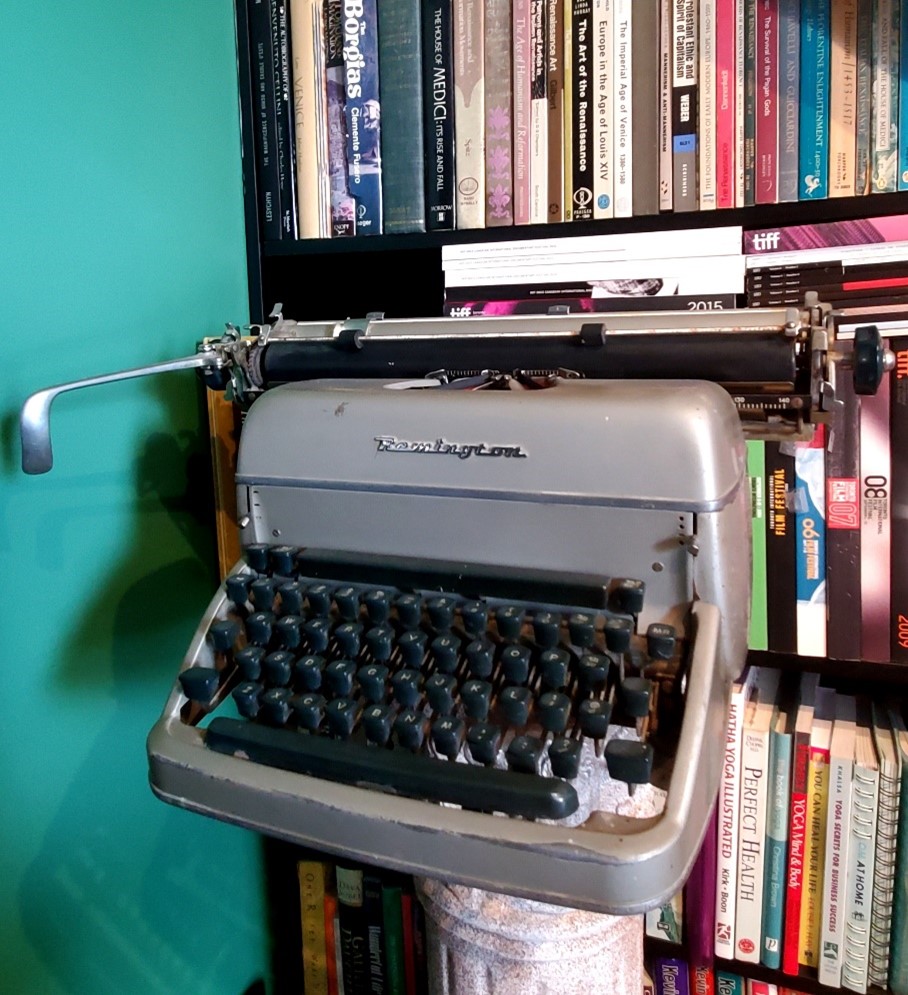

Remington Typewriter

A Nebulous Number of Days of Atomity and Memory

The Spy Who Loved Me

My parents spoke infrequently of their experiences during the Second World War or of their time spent in England, where they met after the conflict. The reminiscences they did share rarely touched upon such traumatic events as having to leave home at the ages of 14 and 16 and never seeing their parents again. But there were some memories they retold more than a few times. One, for example, is how my father and his mates in the Ukrainian Division siphoned off alcohol in compasses of planes in their training camp to make ‘somohonka’ (bootleg liquor). We also heard about how, when my father was taken as a prisoner of war, that in the camp in Rimini, Italy, prisoners were restricted to 1,000 calories a day which included two biscuits. He always tried to save the second biscuit for later in the day, and though my father was extremely disciplined, the hunger was so overpowering both cookies were usually consumed one after the other.

My mother was working in a forced labour situation in Germany, in a hotel repurposed to house German troops as well as their prisoners of war. When sent down to the basement, where the provisions were stored, to retrieve foodstuffs for the kitchen, she never failed to scoop a small handful of sugar into her pocket and, as she toiled during the day, she would dip her fingers into the pockets for a bit of sustenance.

On my elder brother Zenon’s birthday gatherings, my parents would focus on stories about their adventures in Ashton-under-Lyne, a market town in Tameside, Greater Manchester, where my brother was born and spent his first five years. One of my favourites was about the time Zenon gave away my father’s typewriter to a stranger.

My parents had started up a Ukrainian deli in Ashton-under-Lyne where they sold flavourful East European fare such as homemade smoked kobasa and sliced meats. The back of house served as the family home, but also as a headquarters for some anti-Soviet espionage activity. My father was a Ukrainian nationalist with rather extreme convictions, and he was involved with clandestine Ukrainian organizations determined to free Ukraine from the clutches of the Soviet Union and to liberate it from Russian Communism. He was involved in propaganda campaigns and recruiting other Ukrainians to join the fight for the cause, and one of the things he used for this work was the mighty typewriter.

One day, while my parents were preoccupied with customers in the store and my brother was in the rear, a mysterious man came knocking and my brother opened the door (as a child would, back in the day). The story goes that this individual told my brother that my father said he could borrow his typewriter and my brother led him straight to it. My brother let the man take the apparatus and that was the last ever seen of it. My father always speculated that the thief was a Soviet spy because he specifically targeted the typewriter.

It wasn’t long after this incident that the family emigrated to Canada (I was still in my mother’s womb), and settled in Hamilton, about 100 kilometres outside of Toronto. My father was a pillar in the substantially-sized Ukrainian community living there and he was involved in several Ukrainian organizations, some of which were still attempting to undermine the Soviet political regime. All this community work and subterfuge involved many iterations of typewriters, both English and Ukrainian, and duplicating machines such as Gestetners, which I’m sure spewed unhealthy doses of toxic chemicals into our home while infinite numbers of copies of pamphlets, flyers, treatises, posters, and god knows what else were being produced. It was part of our everyday lives and, as kids, we thought it was just normal stuff.

Decades later, my father became an early elderly adopter of computers (with English / Ukrainian keyboards) and fax machines. It was a steep learning curve for him, being in his 70s. He persevered, but he simply wasn’t wired to trouble shoot computer issues. Consequently, my younger brother was often called upon to help my dad and, bless his soul, my brother had the patience of Job.

But there came a time, after decades of heart issues that my father had yet another heart attack and landed in ICU. Unlike previous cardiac events that my father had experienced, while recovering in the hospital, he became very emotional and cried during some of my visits. This was a man who had always ordered his children never to shed a tear or show that kind of ‘weakness’ or emotion. So, I was really caught off guard with his emotive expressions of gratitude for all the sacrifices my mother had made over the years on his behalf so that he could devote his life to the Ukrainian diaspora. He also made a confession I never saw coming.

With eyes filled with tears, my father told me he had lived with so much guilt his entire life. First of all, there was survivor guilt – he not only survived the war, but he was the one person in his family that had the privilege of living a life of freedom in the West and enjoying a relatively abundant life. My parents sent money and supplies to their families in Ukraine as often as possible, but how could one make up for unspeakable hardships such as my paternal grandfather enduring a decade in a hard labour camp in Siberia.

My father proceeded to tell me he had also been part of an espionage ring responsible for sending young Ukrainian men living in the West back to the Soviet Union to conduct dangerous espionage activity. But it ended in much tragedy. There was apparently a mole, or several, and the identities of the men my father and his cohorts had sent to the USSR were compromised and these young patriots were either sent to Siberia or were murdered. My father felt responsible for these deaths and the blood on his hands had haunted him his entire life.

After hearing this admission, so much about my father made more sense and I finally understood why he had lived with such anxiety and physical illness. I also had a much greater appreciation for his emotional inaccessibility and disengagement with his own children.

A few short years later, my father passed. And a few years following his transition, my mother fell quite ill and, due to the amount of medical attention she needed, spent her final two years in a nursing home. During that time, we sold the family home and redistributed its contents. It was a gut-wrenching process, which my younger brother executed almost single-handedly, and I chose to keep only one item from the home – my father’s old Remington typewriter.

My father hadn’t used this particular typewriter in decades, and I’ll never know if it was the typewriter that replaced the one my elder brother had given away all those years ago in England. But it must have had some kind of sentimental value for him as he had gone through several different typewriters over the years, and as mentioned, used a computer the last decade of his life. It’s a wonderful relic and, as a writer myself, this single object holds more significance than a whole household of consumer goods and keepsakes my parents had accumulated over their lifetime.

During this past year, a particular incident triggered my reminiscence of my father having confessed to being a spy. That is yet another long story, but the event led me to conducting some research on another matter entirely, and it led me to discovering some information validating my father’s account while hospitalized – the espionage, the mole, the deaths – it can all be found on the Internet. I have to say, I was flabbergasted once again.

I’ve been highly intrigued, from a very young age, by stories of WWII and Cold War espionage, and I’ve obsessively watched classic black and whites about the war and The Resistance for as long as I can remember. There’s a new generation of these films and a spate of them have been streaming recently – I’ve seen at least three in the last few months alone. And every time I watch one of these espionage tales on screen, I throw a glance at the Remington on the other side of the room.